Antwerp ZOO en Planckendael ZOO save wildlife in Cameroon

Sustainable agreements are gradually making hunting obsolete

Scientists at Antwerp ZOO and Planckendael ZOO have succeeded in substantially curbing wildlife hunting in the Central African nation of Cameroon, particularly in regard of the chimpanzee and the western lowland gorilla. They persuaded families living near the Dja Faunal Reserve to stop hunting these animals for commercial purposes and switch to more sustainable, animal-friendly alternatives. Research Coordinator Jacob Willie: ‘Our three-year project has proven that this approach reduces the threat of extinction for endangered species while strengthening the economic position of local families. This is an important step in sustainable nature conservation!’

The Dja Faunal Reserve is a UNESCO World Heritage Site in southern Cameroon and serves as one of the last refuges for many endangered species, including primates. Nevertheless, despite its status, the reserve is still facing significant challenges due to hunting. ‘In the tropical rainforests of Africa, bushmeat is an important source of food and income for local communities. Approximately six million tonnes of bushmeat are consumed in Africa every year,’ explains PhD student Jacques Keumo Kuenbou. However, these hunting activities pose a threat to endangered animal populations and destroy the ecological balance.

However, these hunting activities pose a threat to endangered animal populations and destroy the ecological balance. – PhD Researcher Jacques Keumo Kuembo

To address these challenges, the Antwerp ZOO launched Projet Grands Singes (PGS) in 2000. The team, stationed in southeastern Cameroon, has been combining scientific research with sensitisation campaigns directed at the local population for decades now. ‘Previously, we tried to protect animals by closing off specific areas or imposing fines, but this only caused conflicts and did not present any sustainable solutions. So, we decided to develop an approach that considers the needs of both the fauna and the local population,’ says Willie. Until recently, there was no empirical evidence that these principles actually bore fruit, but the current study changes this.

A viable alternative

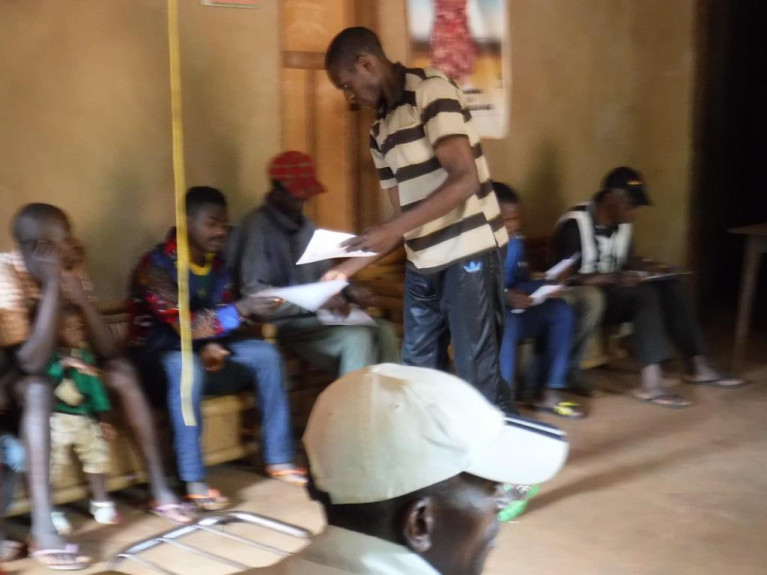

During a period of three years, the team investigated a method in which individuals were personally involved in the conservation project and benefited from it directly. The underlying principle of this project was based on what are called ‘Reciprocal Environmental Agreements’ (REAs). These environmental protection agreements are concluded between the conservation organisation and individual members of the local community. The signatories to these REAs declare that they are willing to diminish their hunting intensity in exchange for technical support in the development of cocoa production and fishing activities. In summary: in an REA, ecological integrity is paired with alternative sources of income.

Jacques Keumo Kuenbou continues: ‘There are around 200 families living in this area, of which multiple members are hunters. Out of the families present in the village for the duration of the project, 86 signed the agreement and 57 did not yet. Collaboration was voluntary. We then collected detailed data on the impact of the REAs on their hunting behaviour, food security and economic situation.’

Measurable effect

At the start of the project, no significant differences could be discerned in the asset positions of either the participating or the non-participating families. After three years, a clear improvement could, however, be noted. Kuenbou: ‘The households who had signed the agreement were able to increase their income by almost 100 per cent. On top of that, their level of food insecurity dropped from 41 to 15 per cent.’ The hunters also spent less time on hunting and more on growing crops. In addition, there was a decrease in the use of firearms for hunting. What is remarkable is that although chimpanzees and gorillas were still being hunted in the first year, this had ceased almost entirely in the following years. This points to a positive trend in wildlife conservation.

Although the approach produced successful results, Kuenbou has noted that there were still a few challenges to be addressed. ‘Younger hunters were more difficult to persuade, particularly because it takes several years for cocoa farming to start paying off. In order to get this group on board, they will need to be offered alternatives that produce faster results, such as working as a bush guide. Neither was there a decrease in the number of traps set in the forest, as this method is less time-consuming for hunters and results in faster profits. In conclusion, increasing their ecological integrity was not a significant factor for some families: they did not sign the agreement because they wanted to save animals, but because they were afraid that their neighbours would disapprove of their primate hunting practices.’

Global potential

Research Coordinator Jacob Willie emphasises the importance of this study: ‘This study shows that REAs can lead to real cultural change. Although the change may be slow, it is surely visible. This approach has global potential and can be applied in various contexts, founded on the basic principle that if people rely on nature for their livelihood, they may be willing to reduce their impact in return for support. This approach to wildlife conservation can serve as a blueprint for sustainable nature conservation projects in various ecosystems and rural settings all over the world.’

This approach to wildlife conservation can serve as a blueprint for sustainable nature conservation projects in various ecosystems and rural settings all over the world.’ – Research Coordinator Jacob Willie